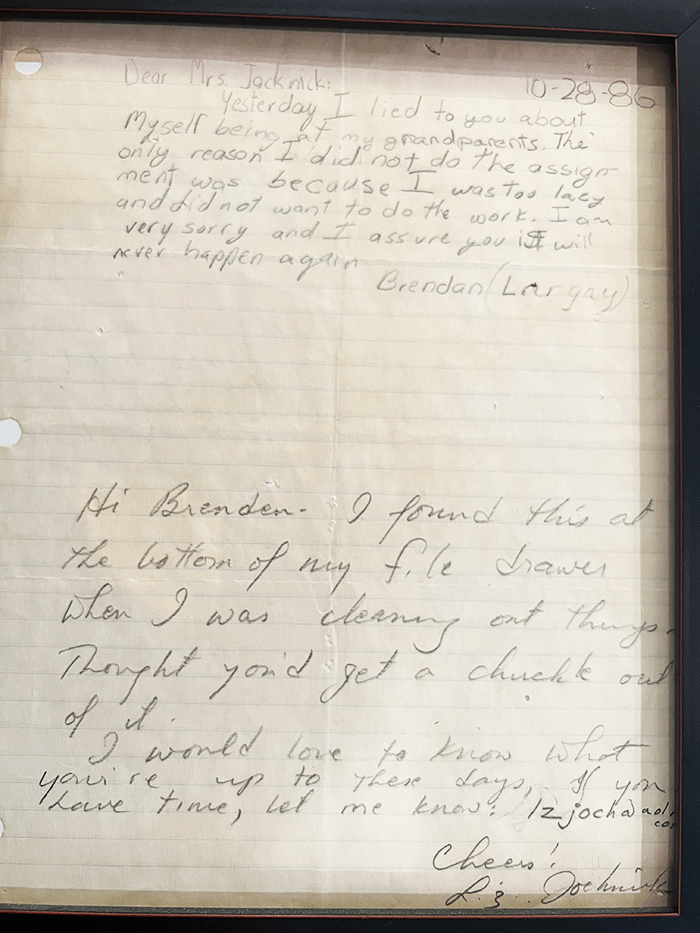

In a frame on the wall of Brendan Largay’s office hangs a sepia-toned note. Although written in pencil decades ago, you can still discern:

October 26, 1986.

Dear Mrs. Jocknick,

Yesterday, I lied to you about being at my grandparents. The only reason I didn’t do the assignment was because I was too lazy and did not want to do the work. I am very sorry and I assure you it will never happen again.

Brendan (Largay)

Underneath it, in the perfect script of a 7th grade social studies teacher, it reads:

Hi Brendan,

I found this in the bottom of my file cabinet when I was cleaning out things. Thought you’d get a chuckle out of it. I would love to know what you’re up to these days. If you have the time, please let me know.

Cheers, Liz

What is Brendan up to? He is the Head of School of Belmont Day School in Belmont, MA where he masterfully uses that little piece of gold to remind young people that failure is not fatal. Indeed, he and I agree that a child who has not yet failed in our PreK-8 schools missed an opportunity to learn from the experience in the safe haven of our educational worlds. Dare I go so far to point out the obvious… you can lie to your teacher and still end up the Head of School someday.

“I was just too lazy.”

“Lazy” came to be a catch-all word to describe a student who needed to try harder to conform to a standard definition of success. When I think of antonyms for lazy – industrious, efficient – learning sounds like industrial manufacturing, not the curious acquisition of new ideas. It is where we were in 1986…and sadly where some may still be.

As is true for many students, Brendan was anything but lazy. He did not attend to his homework that night. Turns out Brendan struggled to attend to more than a night of homework. Brendan had/has ADHD.

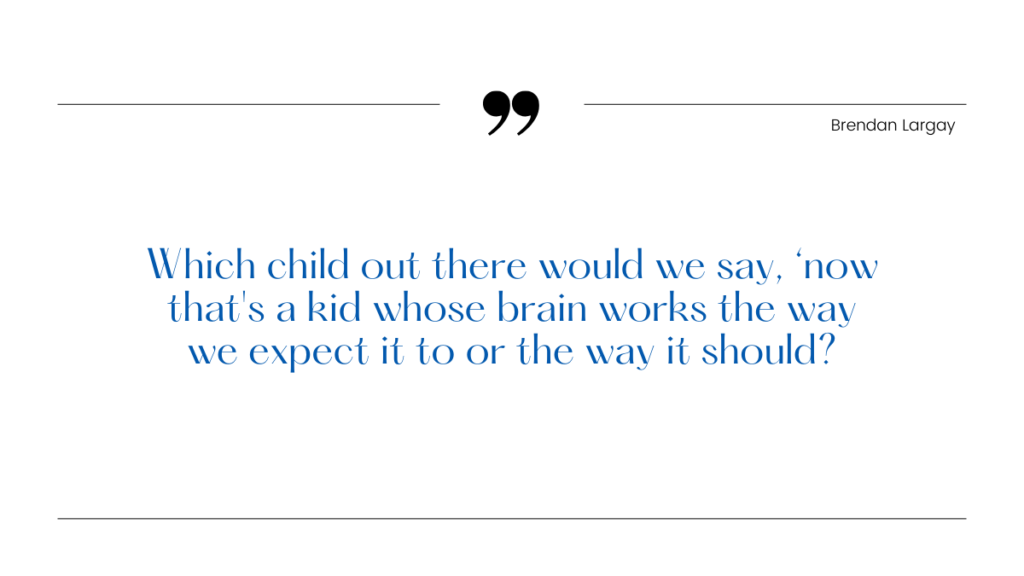

Brendan: To see that genetic gift [of ADHD] being handed down to all three of my children and to watch learning differences play out in different ways for the three of them has me so fascinated by the prospect of how we can make universal the equivalent of a neuropsych or a WISC assessment. Which child out there would we say, now that’s a kid whose brain works the way we expect it to or the way it should? I just think neurodiversity is ubiquitous. And the only way we can effectively lead Pre K to 8 schools through it is if we start to get clearer profiles earlier and earlier of the way kids are wired.

This. The absolute weaving of leadership, learning differences and parenthood as envisioned masterfully by a neurodivergent mind that can attend to the entire problem and ascertain a possible solution – thank goodness he has ADHD.

Brendan is one of the most creative thinkers and leaders I have met. As we walk, I am so grateful to have stepped aside from school leadership, so I can really listen to his ideas. In the past I would be in this conversation listening with the filter of Wheeling Country Day School. How can I do this at our school? Are we failing children by not trying that? When is my next faculty meeting where I could ask that question? And so on. But on this Sunday morning, I have the space to listen.

Brendan: After an ESHA discussion on futuristic thinking by Leadership and Design, I asked my faculty, ‘What is the unsolvable, big, ugly, hairy problem that the world is facing that you want to see solved?’ They came back with poverty, climate change, women’s rights… big, big, big dilemmas. I challenged them, ‘So in 15 years, the 4 year olds who just walked through your door will be 19. They will be sophomores in college. And I’m assuming we want them working on the answer because they will be the ones who both live with the consequences of the answer, but also the ones who have the most pressing need to solve it. And if that’s true, then I need you and your teams to determine what the skills are that will be required to solve these problems.’ And not surprisingly, the skills that came back are both skills that everyone’s been talking about since Daniel Pink and Tony Wagner and all the rest of it. And I would suggest many of those skills belong to neurodivergent profiles, kids who think about attacking problems differently and who have scaffolded some of the structures by which they get there, but have the creativity of thinking and have the flexibility of thinking.

I love this. That is the purpose of education to envision and do our part to enact a better future. I see great power in the faculty working to co-create learning inspired by a man who has the neurodivergent creativity and plasticity to set up such a challenge. Brendan (Largay – reminding you of his last name in case you forgot as he did for his teacher in 7th grade) is the leader we need in schools. And I would encourage any head of school reading this to consider a similar activity with such a strong vision and genuine faculty agency. That fits my definition of education excellence. It also fits my definition of a private school with public purpose. We have the intimacy and flexibility to tackle such problems in this way, so we will. If not us, who?

I would venture to say that Brendan is motivated not only by his diagnosis, but also by the “genetic gift” of watching the diagnosis affect his children.

Brendan: What I can remember most clearly about the dad part of it was just this feeling of like, I have unwittingly sort of set my kid on a really complicated and challenging and difficult path and there’s nothing I can do about it. And that’s incredibly hard. I don’t know if it’s the PTSD of it but I was watching colleagues try to educate my kids in the way that teachers tried to educate me and failed. But now I know better and the teachers are my colleagues.

I went back to that point when my parents very begrudgingly went down the Ritalin path for me. It changed my life. All of a sudden, the “Why are you so lazy?” conversation turned into, “Oh, you’re really smart.” We saw that happen with our kids.

One son fashions himself a political scientist. The 4 year old who threw a block at another child during an admission screening is now a superstar English student, loves history classes and never struggled a day in math. “That would not have necessarily been the path that we would have anticipated the morning of that screening.” When you are in the thick of it, it feels like an insurmountable mountain. The worry leaves an indelible mark, but time reveals a different narrative.

Parenting is not a sprint or a checklist. There is no end point. It is an epic love story. There are heroes and heroines, villains and dragons and parents cannot slay the latter nor claim to be the former. We have to take what is in front of us, validate the emotions, and then do the best we can to keep moving forward. Another challenge is coming. Of that we can be certain.

And so it was two days before Brendan and I walked. He learned that one of his children was struggling in school. The advisor was suggesting medication. Brendan was proud to relay they already had begun medication only to learn their child stopped taking it unbeknownst to mom and dad. I have been in that seat. Imagine the scene: School leader mom (or dad), almost-adult child, doctor “advisor” discussing solutions when the plot twist is revealed. “I stopped my medication.” The resulting action plays out in slow motion and the dialogue takes place in your own head as to your numerous parenting and leadership failures. Indeed, the ego is the enemy.

Brendan: At times it feels disingenuous if I’m being totally honest. There are times when I’m like, Damn, I can’t even figure out my own kids and somehow 339 of them have been entrusted to me. Yet, the very spirit of this conversation is what gets me excited about getting on the plane to come to ESHA in the throes of that situation… or to go back to my school because I feel like I’m fortunate to have the agency to actually be able to elevate this conversation a little bit in my community and within this community of PreK-8 leaders.

Just like that, Brendan moves from ego to purpose… the first lesson of Ryan Holiday’s Ego is the Enemy, Live with Purpose. This walk took place a few hours before we had the opportunity to meet Ryan Holiday at an ESHA retreat, but we were discussing the philosophy of stoicism without even knowing it. Holiday writes “…this moment is not your life. But it is a moment in your life. How will you use it?” and Brendan walks that walk as he elevates personal discomfort into purposeful work to be done.

Brendan then asks, “Do you think this job of independent school leadership is possible to scale? Can we do all the things that a parent is expecting for one child to be true for 339? Or 600? Or 10,000?”

As I listen to our recorded conversation, I am sorry I answered him. I wish I had thrown it back to him and we had debated it more than we did. We would have landed on a much richer, more robust answer. I will have to learn from that in future walks. The comment, “here is a question for you” does not require an answer, only a response of “say more.” We discussed simplifying that big hairy question to a single conversation where a parent, child and special education expert discuss what is best for the child. Brendan likes that scenario, but suggests he would make introductions and leave the room to get out of the way. I urged him to stay and document the conversation. Pull out the threads, the patterns. Use it as an artifact for the universal assessment he sees on the horizon, or as a case study to coach the next generation of leaders.

Brendan: That’s imposter syndrome 2.0. I’m in my ninth year and it’s time for me to be in that coaching capacity. There is a little bit of doubt as you make the slide into coaching spaces – who am I to tell you how to do it better? Despite the fact that I have learned a thing or two in nine years that may benefit others or know the questions to ask, but … who am I to coach anyone?

Hearing him echo what the voice in my head has been saying is surprising. I’m glad I was listening. His question articulated the genesis of these walks. I was asking, who am I to coach anyone, but I was also abbreviating that to “Who am I?” Just as I am kicking around that voice of the imposter in my mind…

Brendan: Allow me to say I just did this very walk yesterday solo and was reflecting on the internal dialogue of how is the school actually doing? How am I doing? How is my family doing? And our walk allowed me to give voice to it…it is so simple and so necessary.

As I try to wrap up our conversation, Brendan sidesteps and asks, What is the next step for you?

As I listen to the recording of his final question, I am unexpectedly captivated once again by the rhythmic soundtrack of feet and the powerful reminder that the most rewarding journeys often involve the simplest of steps.