I love to laugh…even more than I like to make people laugh. Laughter is quite literally medicine for both our minds and bodies. When we laugh, our brains release a cocktail of feel-good chemicals while our hearts beat faster and our core contracts, boosting our immune system and lowering stress hormones. But perhaps most importantly, laughter connects us. We remember our capacity to find joy…simply by letting ourselves be delighted by the world around us.

Liz:The most distinctive thing about you to me is your laugh. It just brings me joy. I mean, I’m glad I now have it recorded so I can just have it on repeat when I want it. Are you as happy as you seem?

James: You know what? I am. I really am. I rarely have a bad day. I think that’s also one of the reasons why I love working at a school because you can find reasons to laugh and to have joy.

I always used to say that I had the best job in the world. Even on my very worst days I could go hula hoop badly with a group of preschoolers and laughter would win the moment.

James: I joke a lot with my team. You will hear me coming because I am probably laughing or joking around or doing those kinds of things. I don’t take myself too seriously, and I don’t think that even on the toughest of days, that it has to be so serious where you can’t find laughter. I remember Geoff Campbell had this incredible belly laugh. We’d get in meetings and we’d start laughing. And we would say, it’s like an instant vacation. Because it is that thing that just completely takes away whatever the space is around you, and you’re consumed by this overwhelming feeling of joy.

I am a genuinely happy person. I really am. I think part of that is just, who wants to be around someone who’s not. If I’m being honest, I don’t. And in positions where I’ve been, I think that also puts people at ease. If I’m laughing and having fun, I think it makes people feel like they can, too. And that’s part of the work. The work is hard enough. We have enough pieces that we’re always monitoring and trying to deal with. So why not be able to have a little fun?

Liz: I think it’s a mistake in this job to take yourself too seriously.

James: Oh, yeah. No question about that.

James Calleroz White is a Head of School. Indeed he is leading the Dwight-Englewood School, his third headship at an independent school. I met up with him on only his third day of school there. As my Uber drove away, I stood on the sidewalk, bags in hand, and stared in disbelief at my worst nightmare – no less than a fleet of emergency vehicles. My heart fell to the concrete beneath my feet. There was an eerie silence that hung in the air that was broken only by the distant and distinct sound of James’ laugh. I didn’t know there had been a single car accident on campus. I didn’t know no one was hurt. My mind raced to the worst possible scenario, but I was lifted straight out of that narrative by the strong, infectious laughter of my friend. I knew everything was ok. That’s what his laughter does. It transports you. And if you laugh with him, you do find yourself on an instant vacation.

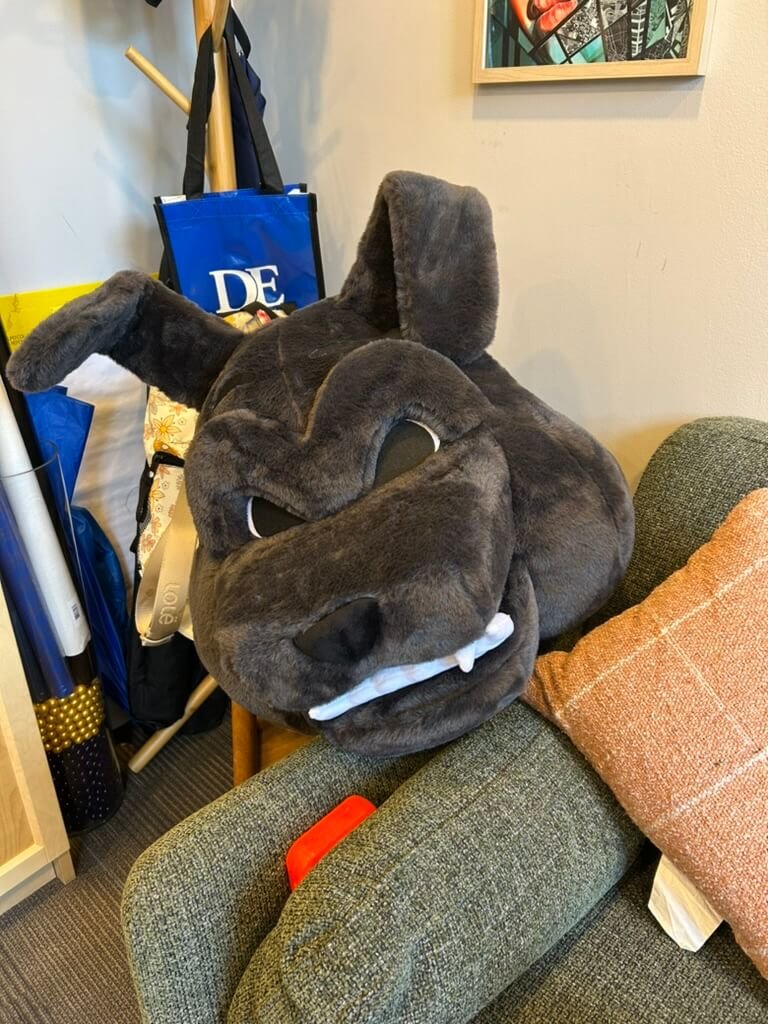

I waited for him in his office sitting next to the orphaned head of DE’s mascot stirring a mix of whimsy and melancholy to observe it divorced from its body and its purpose. I thought to myself, “James wears that,” and indeed he does. Of course I heard him coming long before I saw him, but when I saw him, I rose to greet him and we hugged – an unhurried embrace, a brief pocket of familiarity in the midst of it all. Our hug held a pause – a stillness where everything felt momentarily suspended and peaceful. Nothing external had changed, but everything settled with an old friend just being there solely for the Head of School – it is unfortunate how rare that unconditional support is for a school leader.

Liz: To the guy who doesn’t take it too seriously, who likes to laugh, talk to me about what COVID did to that.

James: It was horrible. It was probably, for me, one of the worst experiences because you didn’t feel like you could laugh. And when you did laugh, you had a mask on. It made me go from relationships to simply tasks. I’m a person who believes in relationships. This idea of connection. When you talk about laughter, laughter is connection. You talk about being with people. Those are the connective tissues. When COVID happened, it immediately became about tasks: making sure you wear a mask, making sure you stay six feet apart, making sure the classrooms are sanitized.

I write like I talk – it’s who I am, right? So I write from a heart space a lot of the time. And when I look back on all the communications, none of that was there. It was all about blue days, red days… so for someone who finds so much joy, it was really difficult.

James: Probably one of the hardest things was when I actually had to get the faculty on a Zoom call to tell them that we were coming back in person. And it was the first time in my life that I felt I was letting people down. Because I knew how scared they were. While I don’t know that I was scared, I knew how much I couldn’t control.

Liz: We were living a science experiment.

James: We absolutely were.

Faculty members said to me, ‘How are you going to feel when one of us dies?’ And so when you live in a world of joy, that’s not a lot of joy that comes in those conversations. For me, It was probably the first time that I can remember, really, that I felt it was personal. And I felt it even though I knew it wasn’t, because most of the time, I joke and say, ‘Hey, they’re not mad at James. They’re mad at the head of school.’ But this was one of those where I was like, ‘No, it’s James. It’s not the head of school. It’s James.’ And in my heart, I knew that wasn’t true. But for the first time, I really felt that.

It is palpable. I do not know a Head of School who does not have a core memory from the pandemic. My first one was being the last person on campus on Friday, March 13, 2020. I stood in the office looking out of the back window where there were normally children digging in the dirt accompanied by the soundtrack of laughter that would please James. What I saw were empty buildings, and I thought, “This is it. I will be the Head of School when Country Day ceases to exist.” As if transforming in a film montage sequence in front of me, the buildings began to look abandoned, the weeds higher, the rocks of the amphitheater cracked… like the dystopia of an unused wooden roller coaster decaying in an abandoned amusement park, my school, my alma mater would not survive this pandemic…and I would be the one to navigate its closure. It was all so real to me even though none of it came to pass.

While the promised two-week closure turned into three months, I woke up everyday ready for the unexpected… ready to pivot… ready to care for every single family in our community. In times of crisis, there is one decision maker, one voice, one face and it was mine… just like it was every other heads’.

Liz: How did you take care of yourself?

James: Not well. I didn’t sleep much. I don’t sleep a lot anyway, but I didn’t sleep much. The relationships that I had with my wife, it was really strained. Because I held on to so much, and I felt like I shouldn’t burden others. And what that did is that created a combustion of sorts that had nowhere to go. Health-wise, probably one of the worst spaces I’ve been in. You think like, Oh, you have all this time. You can be outside. No, that was not the case. And so that was really difficult … tough.

Listen, I think that from a trauma perspective, I don’t know that any of us will truly ever really realize, at least in our lifetime, how much it impacted us.

We did the best in terms of what happened during COVID. School heads, public, private, and so forth, we did more to save this country than I think anyone will ever, ever give us credit for.

Liz: I couldn’t agree more. And yet, we were not trained to do it.

James: Listen, this was not in the manual. Not in the manual. Not in the job description. Oh, my goodness.

Liz: So many things not in the job description.

Jack of all trades. In the moments before we met up in his office, James had been a first-responder, a mechanic, a therapist, an advisor, a trusted friend. During COVID we were scientists, researchers, public health officials, and so on..

Liz: The other thing we know as heads of school is you can’t be all things to all people.

James: But they want us to be. I tell my team all the time, my job is like the Wizard in the Wizard of Oz.

Liz: But no curtain.

James: But no curtain, right? It is an illusion.

Liz: Why is it an illusion?

James: Because I can’t be in every classroom. I can’t be in every meeting. I can’t be in all spaces on my campus, right? So I have the power to change and to curate and to do but I have to trust so highly the people around me.

Liz: And they have to trust you.

James: That is correct.

Liz: How do you build that trust?

James: I think the first piece is, if you say you’re going to do it, do it. Your ethics aren’t what you believe, it’s what you do. And I think trust is not just what I say, it is what I do. I think I also build trust by supporting them. Sometimes even when they’re wrong, we can have those conversations after the fact.

You know how this works, right? We can say things like, ‘That can’t happen again.’ But in the moment, ‘Hey, I’m not going to let anybody come at you.’ My job is to protect as well. And I think that those are the moments that build trust. That is key.

I think the biggest compliment that I can give my team, and I’ve said to them, ‘You make me not worry.’ And I’m like, When I’m not worried about whether you are doing your job or whether the fence is painted or the grass is cut or the kids are… When I don’t have to worry about that, I actually have the bandwidth and the space to actually do my job.

I’ve been a head for now 13 years, which is crazy to me and this was not the job that I ever aspired to be, but I have just a new profound respect for the job… just the ever-changing nature. I hope that ultimately, what is defining in terms of the work that I’ve done is just that I worked hard for the schools, the places, and the people.

James: COVID made me recognize really quickly, and I always known this, but really front and center, how precious life is, how vulnerable these spaces are that we curate.

Liz: I think heads are still just now in 2025 realizing I’m tired. I need a change. I’m exhausted. I can’t do this anymore. What would good support for you have looked like or look like now?

James: It’s so hard to answer that because I don’t actually know, if I’m being honest. I know that there were times when I was really mad because no one ever asked me how I was doing. And I didn’t want them to ask me because I needed them to do something. I just wanted them to ask me because they were thinking it. And then I had people afterwards say things like, Oh, I really wanted to reach out. And they never did. And so what I would say is, Listen, if you are a parent, if you are a faculty member, if you are a board member, if you are thinking that somebody just needs you to ask them how they’re doing, just ask them. They may not need it. But I will tell you, the gesture goes a freaking long way.

And sometimes it is a hug….or a phone call.

James: When I lived further from the schools that I worked in, I was a much better friend because I had time in the car to call people. And I would use that time in the car to call all my friends, high school friends, college friends, just people, colleagues, and whatnot. And so I realized that as I moved up the ranks to become a head, I actually started moving closer and closer to the schools I worked at…

Liz: So I’m never going to hear from you now that you live on campus.

James: No, that is so… Shush.

I lived on campus for six years. For me it was exhilarating to belong to an instant community but created a particular kind of exhaustion. Student crises had a way to seep through the walls with no physical boundary between who you are and what you do. I remember a young girl waking me from a dead sleep to ask me with tears in her eyes to rub her back as she fell back to sleep following the aftermath of a breakup from tumultuous teenage love. Callously, I told her if you lean up against the door jam just right and squirm a bit, it feels like a good back rub. As I shut the door and turned back toward my bedroom in the dark apartment, I knew I had changed. It was time to find a new home. I needed a space where I could simply be human—messy, uncertain, private, real. I needed a kitchen where I could burn dinner without it being student gossip, a front yard where I could water plants without it turning into a parent conversation, or lie in the sun without being shot with a bb bullet… a Saturday where you can exist without being prodded to attend an on-campus football game. But I’ll tell you for years I also missed that irreplaceable feeling of being woven so completely into the fabric of a place that your heartbeat matched its rhythm—the profound belonging that comes from being not just part of a community, but truly home within it and with the people who became my family.

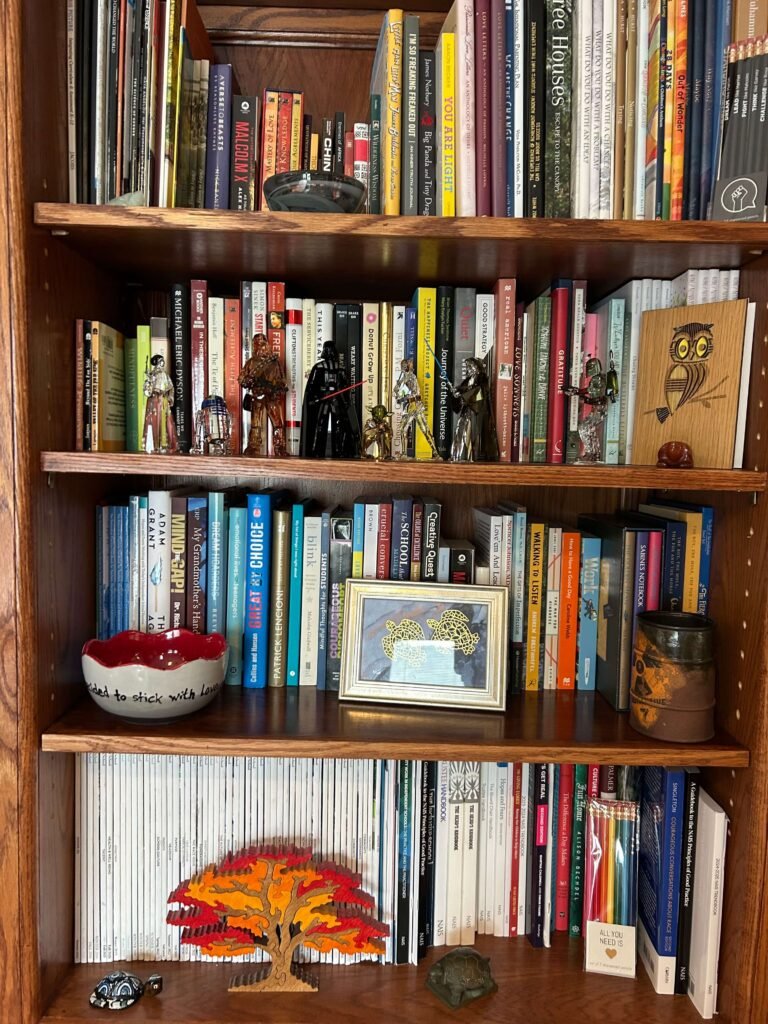

Our homes and in turn our classrooms and offices are extensions of who we are as we curate those spaces.

Liz: Tell me about getting that whiteboard ready when you got here.

James: So you will laugh. When I got here, this office didn’t look anything like this. The wood paneling, older furniture, it made it look like a cigar lounge. I wanted it to be lighter. I wanted it to feel like people could come in here and be welcomed. And also, as a head of school, a lot of the conversations we have, they’re heated, right? So when you walk in this space, it automatically de-escalates. It brings people’s energy down almost immediately. And that’s on purpose.

His office personifies James. It is colorful and full of joy. Every piece tells a story. From the Star Wars glass figurines that remind James we are not alone to the quotes that inspire him every morning.

James: One of the things that I’ve done pretty much every day since I started this is I come in and I find something on there every morning. And that speaks to me.

What’s speaking to you?

Liz: Well, first of all, the You can’t pour from an empty cup speaks to me because I feel like that’s head of school stuff.

James: What speaks to you right now might not speak to you tomorrow or last week.

Liz: I would be remiss if I didn’t ask, how does being a neurodivergent learner yourself impact the way you lead a school?

James: I am dyslexic. I am probably a little OCD, and I am definitely ADHD. For me, I have to remind myself that I’m that because it’s normalized for me. I don’t know any different. And so what I’ve come to realize is that I have to be much more mindful of helping people know what I’m thinking because I don’t think linearly. People think about what’s coming down the hallway and my mind is, ‘What’s around the corner?’ I’m already looking around the corner.

And so my team sometimes doesn’t see it the way I do. I’ve gotten to this place now where I will say to my team, ‘If you don’t see where I’m going, you just have to ask me. If you ask me, I can walk you through.’

It’s just how I think. So when I walk the halls, when I walk around, the thing that they notice really quickly about me is that I notice everything. I see everything. I hear everything. And I notice small things. I notice big things.

Liz: So you’ve made it a superpower.

James: It’s always been a superpower, right?

For many, many years, those of us who had this superpower, we were told that we had a deficiency. We weren’t told that we had a superpower. We weren’t encouraged to use it. We didn’t necessarily have people around us who knew how to help us use it. It’s like when Superman realized he’s Superman, it took him a while to figure out all the things. I think that there’s a lot to be said in terms of the work that we need to do in schools, that it’s not just work for those who are neurodivergent it

… is great work for all kids. If it’s working in one group, we should at least ask ourselves the question, ‘Can it work in another one?’ And we don’t take time to do that.

Liz: And that goes right back to your, if you say you do it, do you do it? If you’re going to accept my child who you know has dyslexia, is he going to be supported?

James: And can you, right? I’ve been really clear with schools where I’ve been the head, saying, ‘Listen, what is the profile of a child that we know we can support? What is it?’ And be honest. Let’s be real.

Listen, we are graduating neurodivergent kids every day, all day. We know that. So we clearly can serve some of them very, very well. And then there’s some that by virtue of the structure, by virtue of how we do things, we won’t. And I think the hardest thing for schools and teachers and educators sometimes to do is to say, ‘I can’t serve your child.’ But I will tell you, it is the thing in my mind that is the most respectful of a child and a family to just own the fact that we can’t do it. We can be honest.

Superman’s power also comes with his kryptonite – for James dyslexia was a superpower except for being asked to read aloud that was his kryptonite.

James: I hardly ever, meaning almost never, read anything out loud. So I don’t write speeches, Liz.

Liz: Right.

James: I don’t write. Because that means I have to read them. And if I have to read them, that means I have to look at that word, I have to process that word, I have to remember in my head how to say that word, and then I have to say it.

Liz: And it stumbles and you’re not flowing.

James: And I realized this when I was asked once to read the names at graduation. And I butchered kids that I had known for years.

Liz: And people didn’t understand.

James: They didn’t. And so after that, I never did it again.

Liz: So you got to take me to, you adopt your son, and then he has the exact same processing that you do. What was that like?

James: I think what it was like for me was that I’m glad he’s with us.

Liz: Yeah. I get it.

And without realizing it, I’m crying. I’m not crying for James or his son. I am crying for Ella. For the baby girl who was born a little earlier than expected with a certain guarantee she would someday have a learning difference. Thank God she did – it’s one of her many superpowers.

So why did I walk with James? He shares with me everything I set out to unpack as I started walking. I had to walk with 45 other people until I finally made the campus rounds with this school leader who understands the fatigue of the position. This teacher who understands dyslexia and how we could better serve all kinds of minds. “What we know is that the pace of some of our schools make kids feel like they’re not smart. My kid is hella smart, but the pace may be too much.” And this dad who understands how beautiful adoption is.

James: Friday morning, January the 30th,

James: I got a call from the adoption person. She’s like, ‘Hey, we just took mom to the hospital. She has elevated blood pressure. We’re going to deliver her today. And I was like, Are you *** kidding me? Like today? Like right now, today? She’s like, ‘How fast can you get here?” I said, “I’m getting in the car now. So I jump up, I grab sweats, get in the car.”

Mistalene was the Dean of Undergraduate Education at Spaulding University at the time. She was running a retreat. I’m calling her frantically. No one’s answering. So I just take off. I’m flying to Cincinnati, right? She calls me as I’m pulling into the parking lot, and I said, ‘Listen, I’m in the parking lot. I’m about to go in the hospital.’ She’s like, ‘I’m on my way.’ So she takes off. I walk in the hospital. They take me straight to the room, put me in scrubs, and he’s delivered maybe 15 minutes after I get there.

Liz: Wow. I did not know that.

I know how his story hits me as an adoptive mom. I don’t know how it impacts you. For James as he tells it, you can see the love for his wife and his son… and his two biological daughters waiting at home for their baby brother.

James: I have a great picture of her holding him for the first time. The joy is just unbelievable. It’s unbelievable. So that’s how Ismael came into this world, and he has been great. And so I’m so grateful and feel so blessed that whatever your belief … that he ended up in our house.

Liz: It was meant to be.

James: It was meant to be.

Do our children know how much we love them? Do they know the joy they bring to our lives? Do the children and adults in our schools know the depths of our conviction and support? I don’t know. Here is what I do know … so far… because I am and will always be a student of life… the more joyful, more calm, more authentic I am…when I am laughing, smiling and curating the spaces and experiences that elicit that, the better my corner of the world is. As Luke Hladek said when we walked, “I’m not trying to take myself super seriously when I recognize that 90% of the most serious problems are not at my doorstep. You know what I mean? So let’s have some fun. If we have an opportunity to have some fun, let’s laugh. We’re teaching kids, we’re in an elementary school, which means we’re all basically a bunch of big kids.”

I wish I knew James when I first started my headship. It’s dumb luck sometimes the wisdom we get and when we recognize it, so let me share this from the wisdom I have gathered on the playground.

The playground teaches us everything we need to know about leadership, if we’re wise enough to learn. Watch a child navigate the monkey bars after falling off – they simply dust off their knees and try again, often with infectious laughter that transforms failure into fuel. Children see through pretense instantly and respond to genuine care over polished authority. Sometimes we need to sit in the dirt during a meltdown. Sometimes the best intervention is simply bearing witness to another’s struggle by asking, ‘How are you?’ The quiet child on the side might just need a moment alone or might be the one who thinks differently and identifies solutions invisible to others. Most profoundly, playgrounds teach us that leadership is not about having all the answers but about creating spaces where others feel safe to fail, learn, and try again – because in the end, we’re all just big kids learning to navigate an uncertain world together. James understands joy creates the connective tissue of community, which tells me authentic presence matters more than perfect performance. We must remember that laughter isn’t just the soundtrack of childhood – it’s the medicine that heals wounds, builds bridges, and reminds us that even in our darkest moments, joy can break through. And like James’ resonant laugh, it instantly transports us to that place where everything feels possible again.