Are you old enough to know Mary Tyler Moore? Do you remember the still image of her broad smile captured as the video freezes on her throwing her hat into the Minneapolis sky while spinning around to look into the camera with eyes that welcomed you to join in her joy?

When I look at the image I am struck by the woman in the background. You can almost feel the generational clash radiating in the moment. There’s Mary in the center, practically glowing with liberated energy, while the woman in the blue headscarf embodies the boundaries she wouldn’t dare to cross. Her whole ensemble contains her – the opposite of taking up space. You can see the generational fault line. Tension creeps in. The writers could only push so far—they’d give us a professional woman, but she would have to be palatable and gracious. Even as Mary blazed trails as a career woman, she still apologized time and again for taking up space. Still…it was a step on the continuum. Obviously, it touched my young heart as the song serenaded, “We’re going to make it after all.”

I hadn’t thought of that moment of television history in decades until I witnessed Luke Felker make almost the same gesture in Chicago a few years ago. He was joyful – no resplendent – to be walking the streets of the windy city reveling in a quick respite from being a Head of School and the weight of expectations that accompany it. As heads we lead and influence that generational continuum – it’s heady work – pardon the pun – so we need time to find ourselves relishing the joy of a moment – Mary Tyler Moore-style.

Luke is my Head of School soulmate. He is my 2 AM call… which is awkward because we have been on very different time zones for 11 years now. He is my Mary Tyler Moore with a lilt in his voice as his words flow unrestrained in pure excitement for the work. When life kicks him in the teeth, as it does all of us, I swear the entire world tilts off its axis. And being a Head of School at The Bay School in San Francisco, CA – especially during COVID – knocked the wind out of him a time or two. His silence would cause alarm momentarily.

Luke: Even if we haven’t spoken in the last month, whatever the case is, knowing you’re out there in the world generally makes me feel better. It’s going to be okay. She’s out there.

We’re going to make it afterall.

Liz: When things were really rough at one point during my divorce, I remember I got a card from you and you said, “I wish I could take you for coffee.” And you sent me just enough on a Starbucks gift card for a cup of coffee. It was just the simplicity of, ‘I see you. I know this is a hard time. I wish there were something I could do. Have a cup of coffee.’

We buoy each other. We build on each other’s energy. It has been crucial to me to have a colleague that I trusted with my strengths, my ideas, and the depths of my challenges and my fears. He shares many of them… as do many of the colleagues who live as heads of schools. Listen in.

Luke: Life is fragile. Schools are fragile, and some schools are more fragile. When you have no money in the bank, it’s a really logical fight or flight… it embeds in us in ways that… One of the things I share with a couple of really wonderful leaders I work with all the time is we’ve all got to take ourselves… in the balloon again.

Liz: In the balloon?

Luke: In the balloon. Well, imagine our work as heads or our work as educators. We’re often right on the ground with kids, whatever the case is. And on occasion, we all need to come up to see. I have this amazing CFO who has not been in schools before Bay, and I feel like he has the ability to ask a question where I’ve forgotten that was possible because I’ve been in schools so long, or let’s say, not exceptionally wealthy schools.

And I’m like, Oh, my God, that could happen here.

Liz: But to the balloon, we think of a hot air balloon, and so you think of blue sky. So I think there’s two reasons to get in the balloon.

Blue sky thinking is like giving your imagination permission to soar without limits, a creative space where you temporarily set aside budget constraints, technical limitations, and that little voice saying “but that’s impossible” – while embracing the hint of “what if it weren’t?”

Luke: Oh, my God. Yes. Well, that’s part of the work that… I mean, that’s what’s been so much fun about working with you is that I feel like we readily go back and forth from land to sky, and there are people in your world who are going to do that with you and that allow you to pause to see things you wouldn’t have seen otherwise. And I think that’s part of what keeps me sane. And why did I come back to ISACS all those years when I was in California? Anything that gets me out of my bubble allows me to see things from a different perspective.

Liz: Just get out of the typical box, for lack of a better word.

Luke: It’s myopic. I adore my CFO. I have to resist talking to him every day. This might be crazy, and… Sometimes he’s like, Okay, I’ve learned more about how the school works, and this is a craziness that is. Sometimes I’m like, ‘Oh, my God, you’re right. Why have we done this? Why does every other school do this?’ He’s like, ‘It’s insane.’

Liz: I like that you said, “This might be crazy, and” instead of, this might be crazy but.

Well, because… AND accepts the crazy.

Luke: … tension is not a negative, it’s a descriptive phrase, and that’s some of the best work we do … If we’re not in tension, we’re probably too far on one side of the spectrum in terms of how we might be leading as a school or a program. You can’t have tension all the time, and you can’t have people being mad at each other all the time, blah, blah, blah. But it’s been like a self-help skill for me ”Oh, tension is a part of my day.”

Not just any tension…we are talking about generational tension. It isn’t the enemy—it’s the very curriculum of our schools. Of course Mary’s breakthrough joy carries the weight of what came before. Of course there’s friction between the woman who tosses her hat in the air and the one who keeps hers pinned down with a proper scarf. I shouldn’t smooth over these differences or dismiss them as obstacles, but rather lean into them with curiosity.

Why does Mary still feel she has to smile apologetically for taking up space? What complex inheritance makes her grateful for scraps of opportunity? Why does her very accommodation—that lingering need to make everyone comfortable with her liberation—stir something unsettled in me?

This is where growth lives: in the uncomfortable space between generations, where the old rules haven’t fully died and the new ones aren’t fully born. Each generation carries both the wounds and wisdom of those who came before. The headscarf generation knew survival; Mary’s generation dared to dream beyond it. Both truths can coexist, creating productive friction.

As educational leaders, we’re constantly navigating these generational crosscurrents—honoring what sustained previous generations while clearing space for what the next generation needs to flourish. How could there not be tension when we’re literally midwifing the future while honoring the past? That tension can be our compass, pointing toward the essential work of helping each generation build on what came before while becoming fully themselves.

Luke: We’re doing generational work around which the communities of the world have been built. I mean, I’ve said things like this to our staff before in a slightly more focused way. I just want to name it, it’s no wonder we might feel fill in the blank, because this isn’t even just about teaching or the way America doesn’t view teachers. I’ve really actually tried to hit the word generational because I think it also reaffirms for teachers that this is something far more than the moment. We’re not just serving ice cream. Not that that’s not an important job, but we’re trying to connect past and future. That’s really heavy.

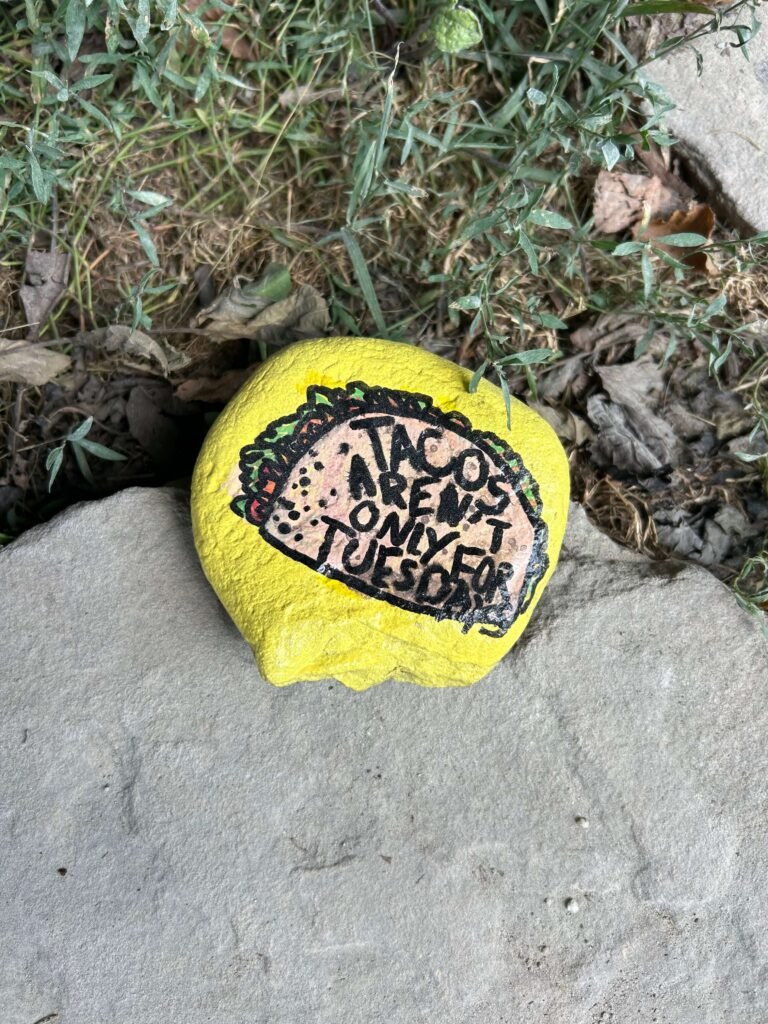

Liz: At times, the very best thing we can do is serve ice cream.

Luke: Yes, that’s true. If ice cream is your jam, Godspeed. For those who have chosen education, how do we help them experience and see the larger arc? Because day to day, it can feel like #$%. We need ice cream. We need snow cones. Something that I’m really proud of. This is a year, too, where I feel like I’m coming to terms with the things I can be proud of and that I can name without being bashful or like, Oh, well, I tried my best. I think I’ve really brought some joy to a very intense philosophical school that took everything really seriously. We have four snow cone days a year that happen on random days. During the pandemic, I was like, On Amazon, we’re getting a #$% snow cone machine for the first day we got back.

Liz: Isn’t that funny? I promised a popsicle party our first day back.

Ice cream cuts straight through the complexity of life, untainted by cynicism or fear. It offers uncomplicated joy that can be measured in scoops.

Luke: And again, it’s not about the snow cone, per se. We need little bursts of things, and kids need it. And to be really clear, adults need it, though they’re less quick to admit it. I think that’s part of the complexity. I mean, it’s part of the beauty of the role. Why do I stay after this many years? Where else could I travel from the dirt all the way up to the blue sky, back and forth with all of these different people dealing with the future of our world, while actually also working with the board where I get to experience really interesting people from a whole bunch of other industries.

Liz: Angi Evans says nobody else gets to work with three-year-olds to 70-year-olds on a daily basis.

Luke: Yeah, and God forbid, you run out of coffee at Grandfriend’s Day. I learned that lesson once, never again. Grandparents eat coffee. It’s an indelible life lessons. I think that’s, again, part of the challenge of the role. It is partly pastor, it is partly tactician, it is partly business manager.

Liz: I think that goes back to support. I can create all kinds of head networks, but it’s still that person that you need that knows the job, that you can say the things you’re not allowed to feel, and they’ll say the things back, whether it’s hard or not.

Luke: Yes. Time a Million.

The Head of School simultaneously holds space for the older board member who believes “children today need more discipline” and the young parent demanding restorative trauma-informed practices. You’re constantly translating between generational languages, validating the lived experiences that shaped each perspective – including your own – while gently nudging everyone to move the needle forward for the sake of generations to come. No wonder we need an unhurried hug hello as I found in James’ office a walk or two ago.

Luke: That’s given me another level of access to sanity… it is finding those two or three people that are always there.

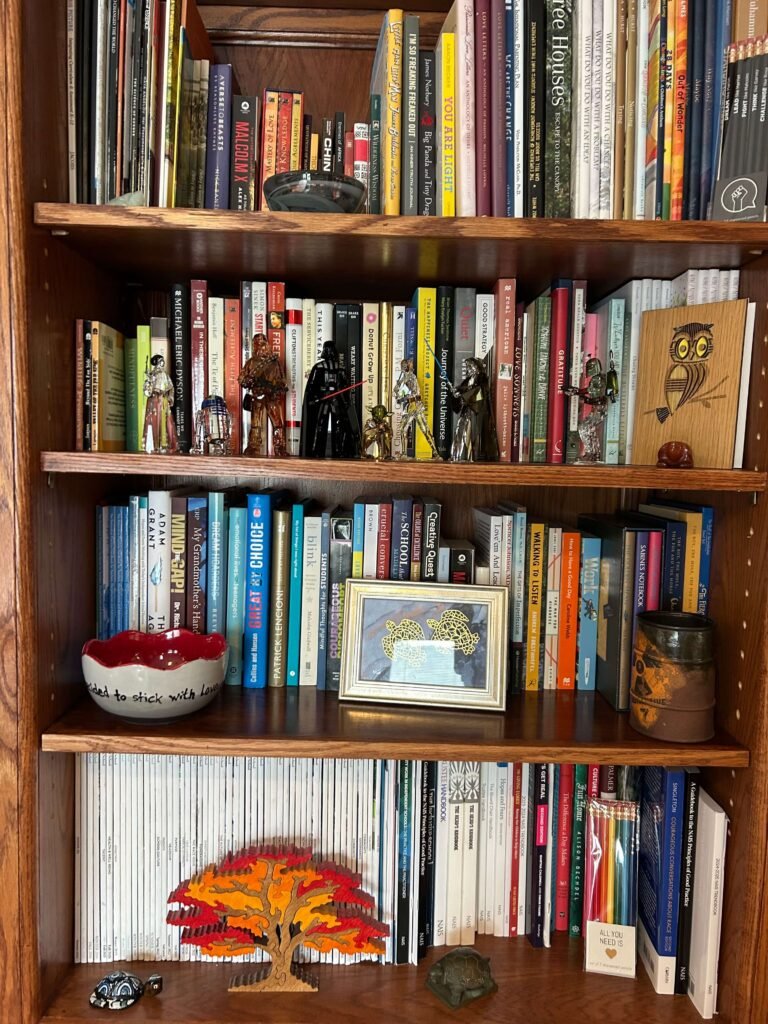

The two other people who are always there and who know the work. Our trio: James, Luke and Liz. In the life-changing work we do, you need a team with which to face off against the generational forces at play. It’s not quite superhero work, but I swear every Head I know deserves a cape. For our trio, I like to think of Batman and Robin, who were incomplete with Batgirl. I’m Batgirl.

Luke: You’re that friend. You make the connections with people.

Luke: I’m constantly reflecting on what you do, how you do it, what you did with Edge, I found and find so inspiring. And there’s still a piece of me who’s like, I can’t even… It scares me. But my point is seeing what you’ve done with Edge or seeing how you lead a WCDS or just talking with you about other schools. It builds the capacity to believe like, “Oh, wait, I could do that. It’s not insane”

Liz: Let’s look up and see. Let’s put a man on the moon.

Luke: Well that’s again part of it, that is the inspiration. On some level, if we zoom out, whatever percentage of things are going to make it or not, we move forward.

The percentages of things that will make it. 100% isn’t feasible. We wouldn’t want it to be. There would be no failures from which to learn. Still, we are timid before we leap into that sky which isn’t always blue.

I love the quotation from Erin Hanson,

And you ask “What if I fall?”

Oh but my darling,

What if you fly?

I always wanted to write those lines on the beams of the shelter where parents waited for our youngest students at WCDS. I thought it would be good inspiration for them as there was always a bird’s nest balanced atop one of those beams. I liked working at a K-8 because it was all about childhood – the innocence of possibility – the hope for the future – the joy of what the day brings as embodied in a bird’s nest. Luke understands. He taught…

Luke: First grade, I taught it for five years. I loved it. I don’t think I could have done it for my whole life. I clearly love crazy jobs, which first grade is. But I don’t think I would have been professionally fulfilled forever. And those years formed me. And it’s so #$% joyful. The whole world is opening up to them, learning how to read. How #$% cool is that?

Liz: And it makes you learn all over again. Yes.

Luke: And we can tell her how to read and go to the pumpkin patch on the same day.

Liz: But come on. When the first graders are still on the playground and not in music when they’re supposed to be because they found a bird’s nest.

Luke: I know.

Liz: It is as exciting to the teacher as it is to the first graders.

Luke: Damn well it should be.

Liz: I woke up this morning with this feeling of, I’ve got to tell Grace she should teach for a little bit. I don’t know. I think everybody should spend a little time teaching somebody something they don’t know for a year …or five.

Teaching lets you embrace the joyful complexity of standing at the generational crossroads— you’re part of an ancient chain of learning. This generation of students teaches you as much as you teach them, reshaping your understanding as you guide young people toward their potential. You become a living bridge between what was, what is, and what could be. It matters…one student at a time.

Luke: To be able to have this conversation today feels so cleansing and empowering, coming back to the reality that if someone doesn’t like it, God speed. Like, great, all good.

Liz: If the head isn’t well, the first grader is affected. And that’s not okay, because to Ella Landini, junior year is not a dress rehearsal for senior year. It is the only junior year she ever has. And the teacher she has damn well better care that my kid learns. I walked with a guy who used to be a teacher… I said, what do you want the teachers of your children to know or to do? And he got real emotional and said, ‘love my kids when they’re not with me.’ And isn’t that what our job is? – we make all the employees feel loved and supported and happy so that they make everybody feel like it’s okay.

Luke: You need people to bring you back to love, to get you out of the policies, the procedures, the fact that we deal with the 2% worst of whatever is happening, because the kids can feel it. I think about how I want to show up. This walk helps to renew the “I can’t wait to be there tomorrow,” I’ll say something ridiculous and silly that they don’t completely understand. But they’ll know, “Okay, that guy, he’s looking out for us.”

Liz: And when you talk about tune back into that love, it’s tune back into that childhood that still lives within us.

I like the idea of child-like wonder: that Mary Tyler Moore-ish unabashed joy that comes from seeing the world through each new generation’s eyes while carrying forward the wisdom of those who came before. I am grateful to think about tension – the ‘both and’ of yesterday and tomorrow. The reminder that all of our generational crossroads are embedded with learning and therefore growth… and that we never navigate these transitions alone. We can send out the bat signal to those colleagues who understand that we’re simultaneously keepers of tradition and agents of necessary change. With them we can take off into the blue sky – how lucky to be accompanied by a creative and strategic genius like Luke Felker.

We are going to make it afterall.

And speaking of the sky… I’ve been trying to articulate the simplest moonshot message as to the purpose of the work Luke and I do. I know it involves the essence of joy. I know it involves a better future. I know it uplifts potential. I don’t quite have it, but then again I haven’t quite finished my walks even though I’ve done 51 of them.