Here’s what I’ve learned from wrestling with a blank page: writer’s block isn’t really about writing…or not writing for that matter. It’s about everything else. It’s about the schedule of the day ahead. It’s about the conversation I had with an old friend moments ago… or even months ago. It’s a voice that whispers, “This one has to be good.” It’s about the gap of expectations – the space between potential and perfectionism.

Maybe writer’s block is really just a necessary pause – that space between stimulus and response where wisdom edges its way in. We have to walk around our ideas – see them from various perspectives – especially in unexpected ways.

Liz: We were talking about what I call writer’s block, but you said you get it even in a non-creative situation. Can you say more about that?

JD: Yeah, not so much creative, but I always try to find something unique or different or something that somebody’s not thinking about, deeper insight into whatever the topic or the business or the issue might be to bring something to the forefront. So you’re not always having the same conversation about the same thing. You’re digging in. In an operating environment, you’re actually identifying and solving an underlying problem in the business or taking advantage of something that’s going well. So what are those things? How can you identify them? Then what are you doing about them? Either to fix them or to leverage off of it.

Liz: So do you try to tell the story of the thing that’s going well?

JD: First of all, what is it that’s just out of the norm so we’re not having the same conversation all the time? Then what are you going to do to fix it? Or what are you going to do to lever off of it? Or when I was in the field a lot, I used to call it, give the client a gift. Tell them something about their business that they don’t know and that you have taken the time to understand or draw insights into from them.

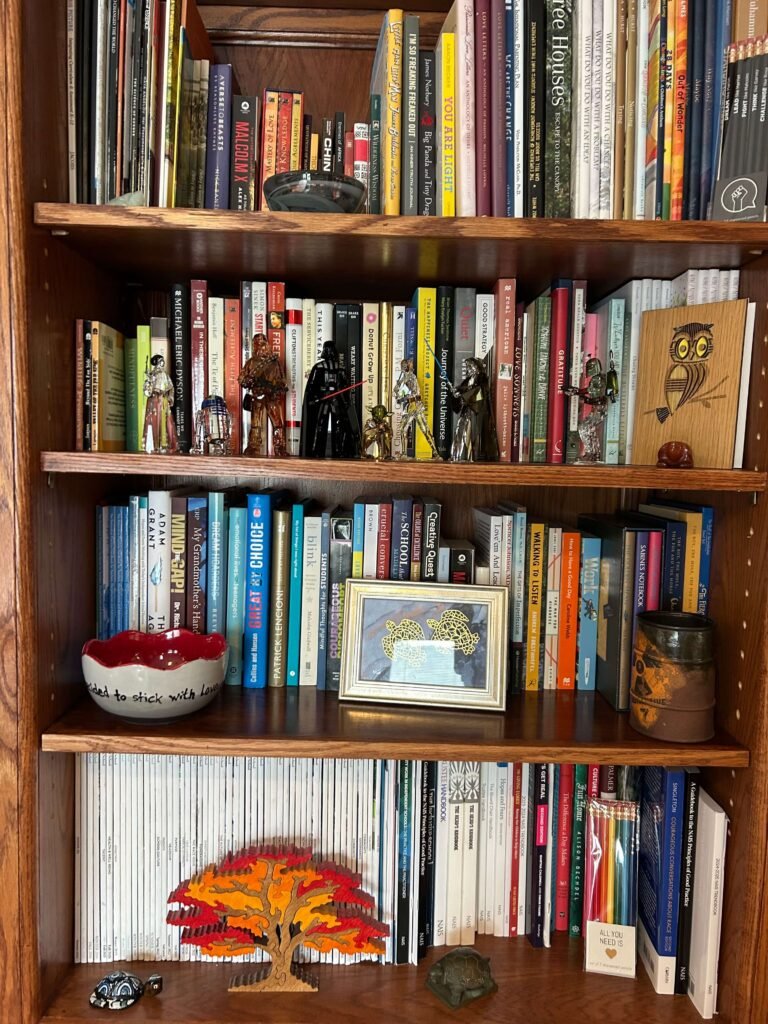

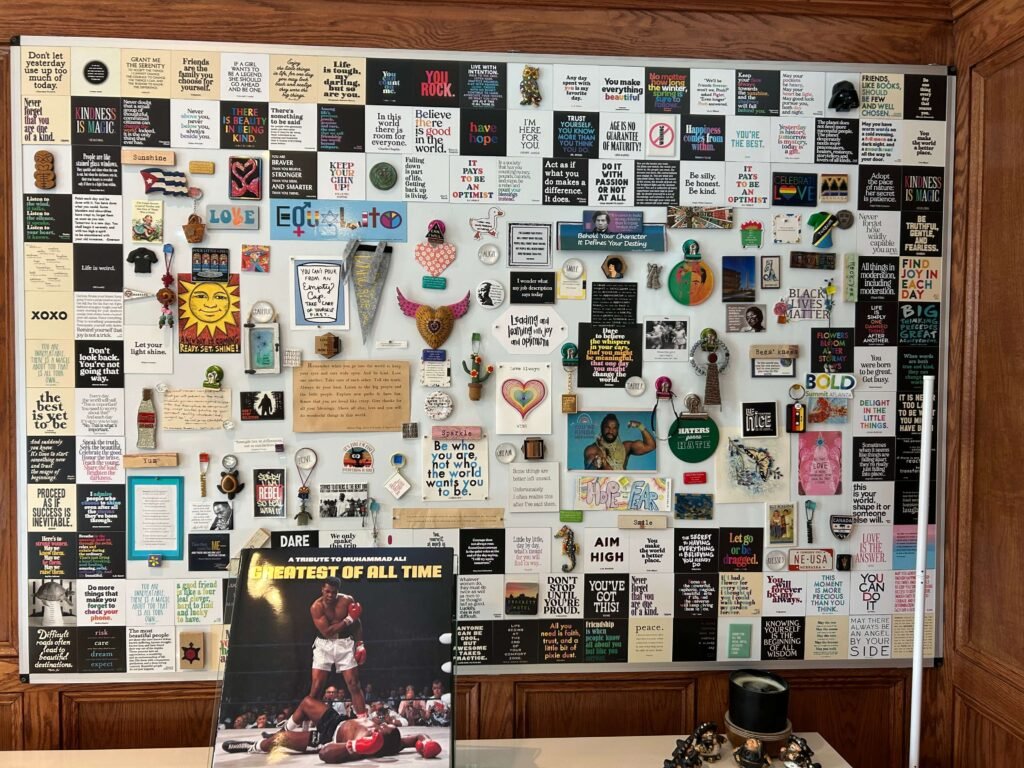

Give them a gift. I’ll get back to how that applies in the business world, but I have to pause. When Jon Grandstaff, JD as I still call him, said those words on our walk, I stumbled. They had that big of an impact on me. These walks are a gift. Individually and collectively they have been a gift to me – grounding me, inspiring me…. stoking my curiosities and highlighting the simple magnificence that comes from someone’s story. I didn’t intend for them to be a gift to the person with whom I walk, but I have found that they are. It is a gift to slow down a hectic day for a walk. It is a gift to be seen. It is a gift to know someone wants to share your insights with the world because they are so profound. As JD says, I tell them something about themselves that they didn’t see as remarkable and draw insights for others.

And some walks offer unexpected gifts to readers and listeners. You hear something that screams, “You are not alone” and maybe you see something in your life a little differently.

Let’s return to JD’s explanation of how this applies to business – perhaps, you are asking yourself what business? – I ask myself that too. I’ll try to get to that answer for you… think of it as a gift coming later.

JD: give the client a gift. Tell them something about their business that they don’t know and that you have taken the time to understand or draw insights into from them.

Liz: Can you think of an example?

JD: In the business we’re in, and you’re in the field with clients, I’d always try to look deeper into the data to tell them something about health care utilization or trend or spend areas or provider behavior that may be questionable, that maybe they didn’t know about themselves. We can be that consultative strategic partner and just not the typical vendor relationship. So you’re of value.

Liz: I love that you were pulling a story from data. Do you live in numbers and data?

JD: All day, every day.

Liz: And yet you recognize that the best connection when you’re with a client or now with your team is more in the storyline.

JD: You have to tell a story from it. What does it tell you? Why? Why do I care about that? It’s the old “so what” conversation.

I love being in the field with clients, understanding what’s working well, what’s not, what their needs are, trying to move a conversation to the next level, get something done with them.

Liz: Why did you like that?

JD: I always wanted to be seen as a problem solver because I never was a sales guy. But I was always looking for ways to grow businesses and grow work that we’re doing with clients, but more from the perspective of being of value.

Being of value. Isn’t that what we all want? I remember Angi Evans admitting her thoughts on retirement, “I matter. In a certain segment of the world. I matter. People notice if I’m not there. I think I will miss that. I’ve become very used to mattering in the world.”

There was something about her honesty and vulnerability that has stayed with me. We don’t just want to belong somewhere – we want to belong in a way that matters and not just for our utility but because we made a difference in a project, or in a life.

I remember thinking years before my father retired, “I wish he would slow down.” I voiced that to a friend of his. He disagreed, “Your father has meant so much to so many people, he wouldn’t know what to do with himself if he didn’t work.” For a brief moment Dad was lost when he walked out of the CEO’s office at Wheeling Hospital. Now what? He didn’t wander far from his patient-centered life. He volunteered at a free clinic and remained a trusted medical advocate for friends and for me. I’d ask him about every ailment my daughters or friends had. I’d ask him for advice on kids at school, for referrals for teachers, and for guidance on our health insurance. The last one always eluded us both.

We should have asked JD. Turns out his business is healthcare finance. As a woman who just navigated private pay through COBRA for herself and her daughters, I have some thoughts on health insurance, but I thought better of disclosing as much and asked JD for his opinion.

Liz: So what’s your take on health insurance in general as an individual, as a dad, as a family member?

JD: I guess thinking about it, it’s one of those necessary evils in life. It’s so expensive and so cumbersome and so difficult. But if you didn’t have it, it would probably be pretty awful at the end of the day and detrimental to many of us. So I don’t know.

Liz: That’s an interesting comment.

JD: It would take so many families and individuals down financially and otherwise. They would not take care of themselves because they couldn’t afford to do it. Even with health care itself already being expensive, they would just not take care of themselves.

Liz: There was obviously a time that there was just a doctor and a patient, and there was a transaction. And somewhere along the way, insurance was born.

JD: Now that you say that, I never have really thought about that. But I assume it was somebody thinking they could do it better or more efficiently or more cost efficiently with this concept of accumulating people into groups and group rating individuals to get better cost. That’s the whole structure of HMOs and PPOs and having networks that you can put people together and spread cost around and you can drive volume to providers that justifies them giving breaks on costs.

Liz: The idea is I just pay a little bit regularly, and then I never get blindsided by a big bill, but I’m also in turn helping other people when they need it.

JD: Yeah. This year, you may not have much of a health care need, and you take certain fewer dollars out of the system, but somebody else has cancer this year, and they’re taking a lot out, so they can average that across a number of people, but keep it low for everyone.

Liz: And you work at the level above all that. Your support is of the insurance companies themselves.

JD: For the insurance companies, inherently …but I like to tell the story that we’re actually, to some extent, working on behalf of the individuals and the members. Because to the extent that we can help manage costs for the providers, it means that the health insurance companies now don’t have to charge such high premiums. If you don’t have to charge high premiums, you can care for more people.

Liz: That’s a good spin on it.

JD: Again, how do you tell the story? It’s about tying into what is my client’s reason, what’s their so what and their why, and their mission and objective is to, most always, provide great world-class care for their members. How am I a part of that conversation? How am I supporting their objectives? In terms of that gift and how I tie what I do to what clients need and want.

Maybe it’s my athletic background or team environment, but I’m all about the team and collaboration. And as I say, sometimes all hands stacked in the middle.

Liz: You mean that moment before you go?

I couldn’t even find the words for the huddle – that moment of pure alchemy before a collective, explosive roar… before hands fly skyward and bodies scatter into formation… before individual goals manifest again. The individual strength in that close circle doesn’t just add up—it can multiply.

JD: Everybody’s got to be on the same page. Everybody’s got know the why. What I don’t do very well… I call it the ‘got you game,’ and I’ve had some very direct conversations with peers and other people about that whole thing.

Liz: In my life, I’ve noticed that direct conversations between people, even if they’re painful, are the only way to move forward. And if you can’t have those direct conversations, then it’s probably not the right place for me. Rick likes to say, ‘Bad news only takes so many minutes, and then it’s over. Stop fretting about it.’

JD: I mean, to the point, whatever I said earlier about being willing to face the brutal facts, whatever they are. I mean, we used to have a saying in my old company. We’d say that bad news doesn’t get better with time. So just speak it and live it and be brutally honest with yourself.

Liz: Oh, be brutally honest with yourself. Say more about that.

JD: You, as an individual, have to be willing to acknowledge and accept whatever it is, good or bad. Everyone will always accept the good, but you have to be willing to look at the bad as well and then challenge yourself with ‘Why was it bad? What am I going to do about it?’

Liz: Except sometimes, can’t we, without someone else… an outsider helping us, can’t we pick the wrong answer to ‘Why was it bad?’ Pick the victimization role? It was bad because of them instead of what I did?

JD: Sure. I try and not always make it about someone else. But all right, so what was our role in what they did? Someone else may have ultimately done whatever. But aren’t we ultimately accountable with them?

Liz: And you can’t change them. You can only change you.

JD: But if we had a better process, a better tool, a better way of this, a better that … better whatever… could we have kept them out of that scenario altogether? Maybe not always, but we should always challenge ourselves.

Liz: I think if I’ve learned anything in the past two years is just to hold space because you don’t have all the information, and if you’re quick to judge or act without all the information, you’re going to be wrong. So if you hold space, there’s something else coming and I can work within this parameter of what I have, you’ll be more successful.

JD: Well, and a lot of that comes from a certain level of trust as well.

One invisible thread weaves through every successful collaboration, productive meeting, breakthrough innovation or just a good walk: trust. Whether you’re leading a team or navigating a difficult conversation, trust serves as the fundamental currency in the transaction. Without it, even the most talented teams crumble under miscommunication, and defensiveness. With it, trust creates a safety net that allows people to take risks, share ideas, and navigate hard times. During one of my hardest times, it was JD I trusted to be a steady, logical presence. It was he who was my safety net.

Liz: I think I’ve learned more about you on this walk than I even knew I would learn. But there was no question in my mind when I felt lost in a storm, You were a lighthouse. And it’s not just because you’re so much taller than I am… There’s going to be a moment where we stop and take a picture, and it’ll be clear to anyone who hears or reads this that we are not of the same size.

JD: We’ll find a rock for you to stand on.

Liz: Yeah, right. Might need more than a rock… but I just felt like, here’s a steady hand that I can hand the controls to. And I’m very appreciative of it.

JD: Well, thank you for trusting me in that. I don’t know that I deserved it. I’m appreciative that you trusted me.

Liz: No, of course you did. And the truth of the matter is, none of us think we deserve those, I don’t know, recognitions, or acknowledgements. But you said yourself it works better when you see the transaction between people as a gift you’re giving. And I don’t think we all think that way… but should.

Maybe writer’s block isn’t about having nothing to say. Maybe it’s about learning to listen to what wants to be said, and then finding the courage to say it imperfectly, authentically, one word at a time…or two.. such as thank you. JD, your steady consistent rational hand gave me peace and helped me navigate through a storm or two. Never as loudly or as clearly as the time you leaned forward as we rode an escalator and you whispered, “as long as you have your girls.” Now those seven words were his greatest gift.