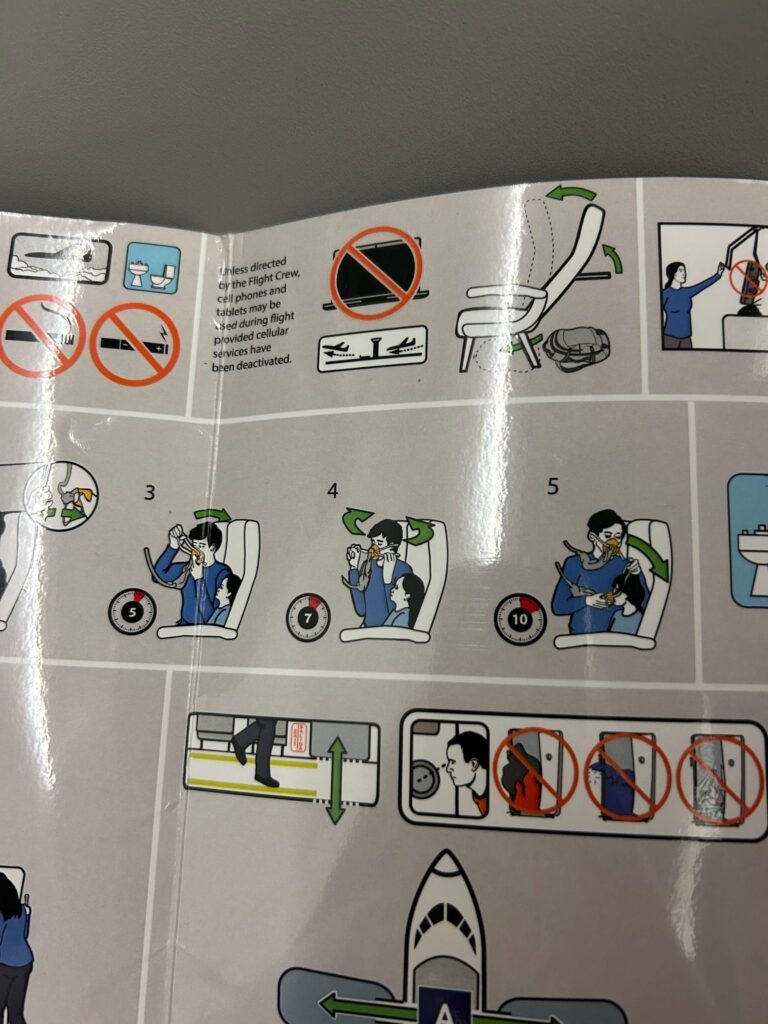

If there is a change in cabin pressure, oxygen masks will drop in front of you. Remove the mask and pull it firmly toward you to start the flow of oxygen. Place the mask over your nose and mouth. Pull the elastic band around your head and tighten. Even though the bag may not inflate, oxygen will be flowing. Be sure to put your mask on first before helping others.

Liz: Of everyone I think of when I think of this expression, you’re at the top of the list. What does it mean in your life right now to put your own oxygen mask on first?

Brean: See, I can’t start speechless. I guess it’s the advice I should be following, which isn’t to say that I’m succeeding on any given day. But I do realize more than I used to, and maybe I haven’t come around to just quite yet, the positive side, I think I realized more in the, “We can’t have me to go down. So whatever that takes and whatever that looks like.” And sometimes that looks like things that are called self care that I never used to do. I have to do that.

As Brean Vaske and I talked, we were walking through Logan Airport, so the actual preflight safety instructions were imminent. Just like on an airplane, if we’re oxygen-deprived, we can’t show up fully for the people who matter to us. The oxygen mask is a powerful metaphor for self-care. It isn’t selfish – it’s practical. You can’t pour from an empty cup.

Liz: What does the oxygen mask really look like?

Brean: Maybe it looks like going to Boston for a weekend and not crying until you are at the airport on the way home.

Liz: That’s a win.

Brean: I don’t know, because when people talk in terms of self-care, I always think that’s a great phrase. But what does it actually mean? And I never really could figure it out because it’s not like I’m going to go spend weekends at spas.

Liz: I took you to your spa. I took you to a Celtics game.

Brean: Exactly.

Our conversation begins with our take on the metaphorical “oxygen mask” — the notion that to be effective caregivers and leaders, we must first take care of ourselves. This theme is particularly significant in this story, as her husband’s unexpected illness thrust their family into a whirlwind of medical and emotional challenges. What follows is an inexplicable story of multi-system failure and recovery.

Brean: I found him in the bathroom throwing up. And I said, “Are you all right?” And he said, “I don’t feel good”. And I said, “Oh, okay.” And the next morning (Friday), I went up and he was still in bed. I think in the 30 years we’ve been together, he’s not gone to work, maybe twice. And I said, “What are you doing?” And he said, “I was up all night. I can’t do it. I called off,’ and I said, “Okay.” And I closed the door, and I brought him all the liquids and went about my business.

Saturday morning, he came downstairs and he tried. He said, “I’m going to go to Lacrosse with you guys.” And I said, “You don’t even look like you can keep your head up. You’re going to stay home.” I got a text about noon that said, “I’m going to go to the hospital and get a bag of fluids. I don’t feel good. I’ll be home by dinner.” And 30 minutes later, I got a text from the neighbor that said, Why is there an ambulance in your yard?

I got to the hospital that night, and they seemed to have it under control. And they said, “We’re just going to watch him overnight.” And I went home. They called 2 hours later, and just kept saying, You need to come. They started saying all of these medical terms because at this point, he was in multisystems failure and it was way above my head, and I didn’t understand what they were saying. So I called Dr. Matt Metz and said, “Matt, what are they saying?” And he said, “They’re saying Kelly will be there, and I’m going to your house.” And I said, Oh, And then I called Dr. Mary Hammond, and those two women came, and they both have medical knowledge that I don’t have. The looks on their faces were like, “Okay, this isn’t good. We’re done.” Apparently, Brian had asked to be intubated. So he had said, “It’s time.”

And then he told them “no ECMO.” I didn’t know what ECMO was. The doctor comes over to me and says, “We need to fly him to Ruby right now.” I said, “Okay, why are we having this conversation? Then fly him to Ruby.” He said, “Well, Ruby won’t take him unless you agree to ECMO.” I said, “Okay, do that.” And he said, “But he said, No.” I said, “Well, he can’t talk now. Do you see the little boy in the corner? He’s going home to that boy.”

There is not much commentary I can offer on the unexpected upheaval surrounding the Vaskes. There’s something surreal about those moments when everything hangs in the balance. One second, life is moving along its predictable path. The next, you’re thrust into a whirlwind of chaos where nothing feels certain—especially not tomorrow.

I’ve been there. That space where time both freezes and accelerates. Where your mind races through a thousand scenarios while your body seems trapped in molasses. These life-or-death moments don’t just challenge our survival instincts; they fundamentally alter how we see everything that follows. We are left shaken with only our faith in what we believe.

Brean: To be honest, at that point, if he was going to die, it mattered more to go see Miles’ science experiment than to stand in Brian’s room. Miles and I talked Monday on the way to school, and I said, “You know how we can believe in things we can’t see?” And he said, “Yeah.” And he quickly corrected me, “But dad doesn’t. Dad believes in science.” I said, “He does. But the two of us are going to believe in the things we can’t see. And dad’s going to believe in science, and dad’s going to come home.” And at that point, Miles and I, I think, we were the only two people in the world who believed that. We knew he was going to come home.

Liz: You know, I’m a really big believer in generational trauma and generational continuation. And the woman whose father died when she was eight was facing her son’s father dying. And you didn’t let that happen.

Brean: I told them, I don’t know anything about this, but I know how to make decisions. So if the question is something that gets him closer to home, the answer is yes. And at one point, they wanted to cut him open and see if he had a perforated wall, and I knew we would never get him closed. And that’s a rabbit hole we’re not going to go down. That’s farther from coming home. So that’s a no. And that’s how we made all decisions. And you’re right. Part of it was my father actually died of multi-systems failure, and that’s what Brian was in. And I said, “We’re not doing this again.”

He spent two and a half weeks on full life support. They fully believed when they pulled that, he would die. They pulled it. He spent another month and a half, I think, at Ruby, followed by three weeks in Weirton and three weeks in Sewickley. I decided that I was going to take Miles on our annual trip. We go to the same beach with anywhere from 50 to 100 of my family members, all of those family members who had kept us afloat for all of those months. And I decided we were going to go. Brian was no longer going to die. He just needed to get stronger.

They called while we were at the beach and said, We want to send him home. And I said, “Well, there’s no one there.”

Liz: This is my favorite part of the story. The woman who had one goal, which was to get him home and made every decision accordingly, when it was time to get him home, said, “No, I’m at the beach. Give me a sec.”

The aftermath is where the real work begins. Brian survived, yes, but survival and returning home to the life they once knew are different creatures entirely. Brian is blind as a result of his harrowing experience. The ground beneath them feels unstable, as if the earth itself has forgotten how gravity works. Routines that once provided structure now seem impossible.

Liz: But the pain lasts. And in your case, you still need your oxygen mask. But now they brought him home and you got nothing. There were no services for your now-blind husband who could no longer do his job as a pediatrician.

Brean: Correct.

Liz: I’m not saying the services don’t exist, but you don’t know what you don’t know.

Brean: On my days of some energy… which I’m going to get back to full strength, but I’m not there yet… I wonder, because I like to fix problems, what I could do to change that – the things we still don’t know. We are still waiting to hear from the Department of Whoever to chase down the paperwork alone and apply for the things and deal with the…

Liz: What I hear and what you just said is you like to fix things. You like to be in control. You’re used to making all the decisions. And so when you don’t know about something, do you beat yourself up that you didn’t know?

Brean: Not that I didn’t know, but occasionally that I don’t have the hours or the energy to do the research that he deserves. But my kids fed. The homework is done. So that’s the part I struggle with. I wish I could fix it and dive into it the way he deserves.

Liz: Maybe this month’s oxygen mask is just getting to the end of the day and saying, what I did today was enough. That would be a good oxygen mask for you right now.

Brean: I had to tell myself very early on because I was making dumb mistakes that I don’t usually make. And not in terms of serious things, in terms of, Miles needed that last Tuesday, not this one. Dumb mistakes. And I had to remind myself that I’m actually not dropping any more balls percentage-wise, it’s just the number of balls in the air has increased.

I love that the former college basketball coach still uses the lens of her shooting percentage to gauge her success. Getting back on your feet isn’t a linear process. Some days you’ll feel almost normal, but your nervous system remembers even when your conscious mind tries to move forward. What nobody tells you is that it’s okay to wobble. It’s okay to take tentative steps. It’s okay to rest when the weight of it all becomes too much. Finding your footing after brushing against mortality isn’t about “getting over it” but about learning to carry it differently. You will drop balls. Lots of them. Children inherently know this, so Miles gravitates to the practical silver lining.

Brean: He spent weeks and weekends and did all of these things that I know that 21-year-old Miles will be better for, 25-year-old Miles will be better for, husband Miles will be better for, because he went and stayed with my aunt, who’s a retired children’s librarian, and she took him to things that it wouldn’t dawn on me to take him to. And he has asked this summer to go back. She is, I don’t know, close to 70 years old, and he wants to go back and hang with her and do some things. So he has realized the benefits of the very large family.

Liz: But that’s a beautiful gift of reframing, because at one point, you were framing it that he’s being shuttled off to all these people. And what you are realizing is that that’s not the way he saw it. These were great opportunities. That he actually wants to repeat.

Brean: He feels a part of a community that helped us. So I know he will be better for it.

No Mud, No Lotus.

I was given the book by that title years ago. Thich Nhat Hanh subtitled it, The Art of Transforming Suffering. He writes, “Most people are afraid of suffering. But suffering is a kind of mud to help the lotus flower of happiness grow. There can be no lotus flower without the mud.” It requires us to reframe the storyline we write in our minds like Miles and his mom are doing.

Miles and I have been connected for nine years. He was a student, who at age four referred to me as “Lunch Lady.” It makes perfect sense since he saw me most often during lunch. I was important in his orbit only because I opened things in his lunch box for him, not because I was the Head of School. Brean and I bonded over the humor. Ironically, he interrupted by saying “You should probably go to the beach and have a break – a day off because you’ve been working so hard.” At four, Miles knew about the oxygen mask before the two of us did.

Miles’ mom and I have been connected since that night last May in 2024 when she called to talk about the possible regret of not taking Miles to see his dad… just in case. I listened. I offered advice, but mostly, I listened. In the weeks that followed Brian from being the sickest man in the hospital to his return home, we texted. We invoked attorney-client privilege that wasn’t actually the case …although she is a lawyer. We said aloud to each other the things you are sorry you are even thinking by invoking “Oklahoma” from the likes of Ted Lasso’s honesty. Our conversations can still be raw. We made a pact to show up honestly even when it is unfamiliar or uncomfortable. I needed it as much as she did.

When Ashley Battle offered me a second ticket to the Celtics game that followed our walk, I called the former basketball player and coach who would see this trip as a pilgrimage to her Mecca.

Brean: Going to Boston for a weekend and not crying until you are at the airport on the way home was a big step. And to be honest, you did it in a way that it had to be done in. There wasn’t a lot of time to think it through. There wasn’t a lot of time to talk myself out of it. You dangled the appropriate carrot, with the appropriate time – not very long, two days. It was a Sunday to Monday. Sunday, if everybody sits on the couch and watches a movie and they eat pizza, it’s whatever. Monday, Brian goes to Seeing Hands all day, and somebody will play with Miles. Everybody has been great.

They say a caregiver holds your hand through the darkness. Brean did that literally. She learned medical terms she never wanted to know. She advocated and made decisions when Brian had no voice. We need to do better by the caregivers: resources that extend beyond the patient to embrace those doing the daily work of supporting recovery. Spaces where they can speak their truths without fear of their seeming disloyal or ungrateful.

Because here’s what I’ve learned: no one recovers from any amount of suffering alone. The hands that help lift us back on our feet need support to get back on theirs too.

I am confident Brean will get her footing. So is she.

Brean: I think the way that you build confidence is demonstrated performance. And for better or for worse, I have a lifetime of things that didn’t go as planned but we figured them out. So I do have a lot of faith in my ability to figure it out, even though I don’t know what it looks like yet. Give me some time. I mean, it’s the story of my life, but it was taught to me. When my dad died when we were little, my mother said, “We’ll figure it out, and we did.” It didn’t always look pretty, and it didn’t always follow the game plan, but we figured it out. And so I guess that’s a skill, maybe. A skill? Can I call it that, that we learned from her. And like I said, it didn’t always look like we were figuring it out, but we were.

Brean, you are more than figuring it out. And you are not alone. You know that now. Look to your side. See those walking with you. Recovery doesn’t happen in isolation—it happens in community, in the recognition that life’s most profound challenges are meant to be shared. We just need to remember to put our own oxygen mask on before helping others.

—

Upon finishing the piece, Brean texted, “As I read it, you make me sound like a superhero.”

I responded, “I see your cape.”

That is the thing about facing an unexpected challenge in life… it becomes our reality and we are just doing the very best that we can…sometimes barely breathing. To the outsider it seems you are performing feats only a superhero could …because we cannot imagine that same fate in our own lives. We cannot dream that we would have the same strength to face it. But we do.

We may never see ourselves as the hero, so we need to walk with someone who sees us – even at our messy, authentic best.