In 1995 my love affair with the moon began. Professor Eleanor Duckworth introduced us. As part of her T440 (Tea for 40) course at Harvard Graduate School of Education, she required us to keep a moon journal. She asked us to write down every time we saw the moon – what time it was, what day it was, where it was in the sky and what it looked like. We could draw what we saw. We could simply write. Regardless, we needed to pay attention to the moon … consistently.

It was hard to explain to my dad that I was moon watching as part of my masters at Harvard. Let me put the assignment in another light for you. She made us, as educators, become learners together. She asked us to learn about an object we thought we already knew. She didn’t tell us anything to watch for, nor give us a rubric for how to get an A in moon observation. She just asked us to pay attention and to keep a moon journal.

The assignment wasn’t about astronomy. It was about learning to be learners. Stumbling around Belmont, MA in the dark, I was experiencing firsthand what my students feel: the discomfort of not knowing, the thrill of discovery, the way understanding emerges slowly from patient observation rather than quick instruction.

This brings us to one of Duckworth’s most counterintuitive insights: not knowing is far more valuable than knowing… and I would add, far more fun. Think about the last time you watched or listened to a young child encounter something new. They ask. They tinker. They hypothesize. “Mountains actually change shape when you drive around them.” or “There are more steps going up than going down.” When children wonder and come up with their own ideas, it’s the same fundamental process that scientists, inventors or artists do. Duckworth calls this “the having of wonderful ideas.”

Liz

We were just talking about Eleanor Duckworth and her work of the Having of Wonderful Ideas. And the second piece of that is, and kids should have a wonderful time having them. And I feel like that’s what this is.

Jane: We try.

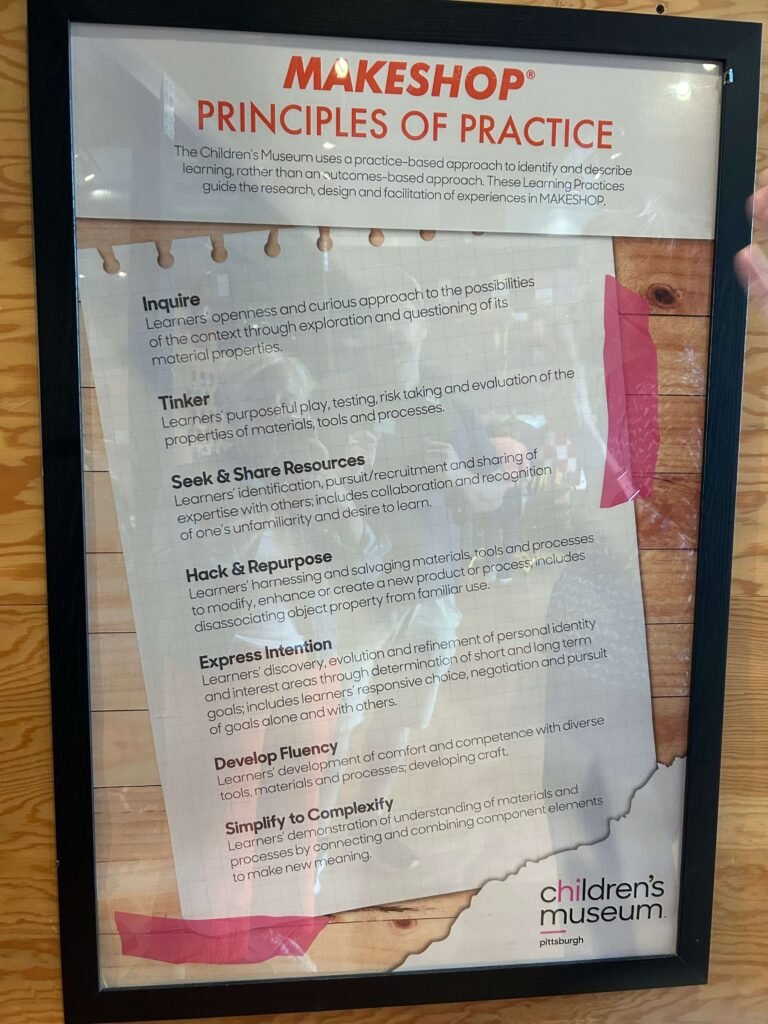

If you want to see Duckworth’s theories of how people learn in practice, look no further than the MAKESHOP, developed under the leadership of Jane Werner at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh. Just like Duckworth’s moon-watchers, visitors to MAKESHOP don’t come to be told facts. They come to explore, to tinker, to have wonderful ideas.

Jane

I always say that a three-year-old loves to sand. I mean, I’ve watched a three-year-old just sand away. Everybody can be makers. The day that I saw a grandfather sitting and making a pin cushion for his wife, I was like, Yeah, we got something here. This is pure gold.

And I keep thinking, you can do a maker space with nothing.

Liz

With nothing?

Jane

Yeah. Really. Cardboard, some yarn.

It’s not the sophistication of the materials that matters—it’s what children (of all ages) do with them. A child who discovers that cardboard can be folded to create strength, or that a broken toy can become the foundation for something entirely new, is engaging in the same fundamental process of inquiry that drives all scientific discovery.

Liz

But you don’t need all that. You don’t need the circuit kits.

Jane

Yeah. These are actually stuff that kids have taken apart.

Liz

Yeah.

Jane

Here. … Look at this. Actually, I like that part of it, right? It’s like, oh, my gosh, you can do this. This is stuff that you can do at home. How simple is this? A little motor out of a toy. Now you’re ready to rock and roll. And some batteries.

Jane engages in the process of making a circuit herself. When I asked Jane to walk, I knew we would need to stop and play. We were in a children’s museum afterall. Our inner child never lives very far beneath the surface wanting to mess about and wonder in our own thinking… if we let it…and we really should let it much more often. Listen to her thinking…

Jane

I’m curious about what this one does. These are all new. There you go. They go slow. One of these goes very fast. Hmm. I did that wrong. Is that going to work? Yes.

Liz

Wow.

Jane

See, that, you should have videotaped. I put a switch in between. It’s fun, right?

Liz

And it started with $5,000. Yeah.

Jane

And we didn’t really need $5,000. We bought a couple of sewing machines. We bought some tools.

Jane explains how the MAKESHOP began.

Jane

It’s a little bit of a longer story. I went to the second Maker Fairs at San Mateo. I had a friend who was a neighbor of Dale Dougherty , who was the founder of the maker faires, and the whole maker movement out in California. He said to me, “My neighbor’s doing this really interesting thing that I think you’d be really into. Why don’t you come out?” So I did. I needed to go out to San Francisco for something else, but then I tacked this on. And I was blown away. There was one whole tent that just had sewing machines and piles of old clothes, and people were reusing the cloth. I’m a sewer, so I was like, That’s so cool. I can’t even describe it.

Back at the museum in a meeting with the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University (ETC), someone

proposed this idea that was basically a maker thing. “Well, I want to do that.” So he and my friend from ETC, we all got together. I said, I have $5,000. I’d like to try this out this summer. So we actually put it in “The Garage.” It took off. Adults and children were here, then it suddenly was this thing.

When she says it took off, she means it.

Jane

I think we’re up to over 400 maker spaces across the United States, actually, now that we’ve been helping to put in not only schools, but hospitals.

Liz

So 400 that you’ve helped to put in?

Jane

Yeah, because we partnered for a while there with Google, and Google was funding them, and that was a great partnership. But each of the schools, each of the spaces are unique to the school or the institution. We have one in Western Psych. We have one at Children’s Hospital here. Those are two very different spaces. We also do professional development because these things do not go anywhere unless the teachers are really dedicated to it.

This is what we were doing in T440, learning to be dedicated to responsive teaching. Eleanor Duckworth would sit cross-legged on the floor, a collection of ordinary objects spread between her and an eight-year-old child who had been invited to explore with her. Around them, up to fifty graduate students leaned forward in their chairs, notebooks forgotten, watching intently as Duckworth’s gentle questions unlocked the child’s thinking. “What do you notice about what happens when you…?” she asked, her voice carrying genuine curiosity and then listening as if she’s never heard anything more important, asking follow-up questions that honor the child’s reasoning while gently pushing thinking forward as they are messing about. This is learning as it actually happens: messy, nonlinear and absolutely real. It takes patience. It takes practice. It leaves room for all kinds of minds to show off their learning.

Jane

Everybody learns differently, right? So I always have to just laugh a little bit when people say, I’m neurodivergent. I’m thinking, so am I, and so are you, and so are you. Because we all learn differently.

We do all learn differently. Duckworth explained in a Harvard convocation, “Helping people learn involves honoring their confusion. This is what keeps minds working. I’ve found that if one idea is presented as the right answer, thinking stops.” Thinking doesn’t stop at the MAKESHOP. Indeed by looking at everything from the eyes of a child, Werner and her staff create the moments that unlock thinking. Ella likes to remind me “Not everything has to be a teachable moment, Mom,” but I disagree. If we choose, we can learn something from almost every moment.

So let me take this moment to learn more about the ETC, a masters program and interdisciplinary research center founded by two co-directors; Randy Pausch, a Computer Science professor (and yes – the man who delivered his inspirational Last Lecture), and Don Marinelli, a Drama Professor. What a pairing – drama and computers. To quote the CMU website, “To this day, the ETC is one of the most inventive and impactful programs in the world. Randy Pausch liked to say that the ETC is the world’s best playground, with an electric fence.”

It perfectly captures what Duckworth knew about wonderful ideas—learners thrive when we allow them to mess about while taking their questions and their ideas seriously. It is what is happening under Jane’s leadership at the Children’s Museum and in her partnerships with the ETC.

Jane

We’re just doing stuff and saying, Isn’t this interesting? … you take it from here. I mean, that’s why every maker space has to be different because everybody has different talents. They have different viewpoints. They’ve had different lived experiences. So use that and then just try to find the next edge. Just keep trying to find the next edge. So that’s what Museum Lab is all about, is looking for the next edge.

Liz

It feels like it’s a make shop on steroids.

JaneThat’s exactly how I describe it. For older kids.

She looks for the next edge – pushes the envelope – but makes sure the experience offers everything it can for the teachable moment. It is how they build exhibits.

Jane

So that’s what we do. We test and prototype.

Liz

So how much input or how often are you sitting in a meeting when an exhibit is being designed?

Jane

Not as much as I used to. I mean, that was my whole thing. But now I try to stay out of it because it’s not fair. We have the Charlie Harper setting up right now. Do you know Charlie Harper?

Liz: I do not.

I’ll spare you the hours I spent learning about Charlie Harper as I was writing this, but as I explored his art, I knew Eleanor and Jane would be proud.

Jane: He’s a West Virginian. He actually grew up in Buchannon. And he became a big-time graphic designer in the ’60s. He’s big with the mid-century folks. He did all the National Park posters. If you saw his work, you would be like, Oh, yeah.

So we have a partnership with his estate and his son, and we did this exhibit on Charlie Harper and Biodiversity. I really stayed out of it. They did the prototyping, and I have to say it’s the first time in a long time I went back to them and asked, “We’re traveling it, right? This isn’t good enough if we’re going to be doing biodiversity. This is a great exhibit about Charlie Harper, but very little about biodiversity.” To their great credit, they went back in and are prototyping some exhibits around biodiversity.

Because if it’s not right, we’re selling one thing, and they’re getting something else. And people notice. We have to make sure that our quality stays really high. For kids. I mean, it’s for kids.

When Jane says, “It’s for kids,” that means it is even more important to get it right. You can hear it in her voice. I am not sure that is the case when others say it. It should be.

There is an irony to the MAKESHOP and its location within the museum.

Jane

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was here. We actually took that out. I thought, “Oh, my God, Pittsburghers are going to hate me forever.” And then we put the maker space in here.

Jane

I always say he laid the groundwork for the rest of the place because he was just so influential in all of our lives, all the people who really expanded the museum. I really learned a lot from Fred. Fred was like the stars and the moon. But I love Joanne because Joanne was just like the water and the Earth. Every time she saw you, she would grab you and she’d say, I love you. You know how much I love you? And she meant it. She was just very funny and she was straightforward. She said things like, “Don’t make him a saint. Don’t ever make him a saint.” I’m like, “Okay, I got it. I won’t.”

Everybody says, “Oh, what would Fred do? What would Fred say?” I’m like, What a mistake. I mean, you have missed Fred Rogers completely if that’s what you’re thinking. He wanted you to do great things for kids. So what are you going to do? And what are you going to say? I think that that’s the better question.

Great questions, Jane. What are you going to do for children? This is why our world needs Jane Werner. She has kept childhood front and center since she began at the museum in 1991.

Jane

They called about this job being the Director of Exhibits and Programs. I thought, That’ll be easy. They’re a little place. I’ll do that for a couple of years. I’m thinking about having another kid. It’ll be easy. Easy peasy. Then I’ll do something else. And then here, one day to the next.

Well, we were 20,000 square feet. Actually, when I started, we weren’t even that, because we only had the basement and the second floor. The first floor was still history and landmarks. So it was little. It was 5,000 square feet total, let’s say. And now, that whole complex is ’80, and this one is ’40.

The larger complex is the Children’s Museum and the smaller one is the Museum Lab designed with middle school students in mind. Both are the very places where children mess about to learn and adults listen just as Mister Rogers and Professor Duckworth did – both cross legged on the floor, chins resting on their hands, eyes as wide as the child’s with authentic wonder.

It’s time to push the edges again, so Jane’s team is developing a new exhibit with Eli Lilly on character.

Jane

We want to explore some other things. This character thing is really interesting to me.

Liz

Especially when you talk about the mental health piece.

Jane

Right. I mean, it’s fascinating. And we’re working with the Fred Rogers Company. And the discussions about character I didn’t think would be so contentious. I don’t know why. It’s fascinating to me.

Who is to say what’s right and what’s wrong? I mean, there was a moment in time where a younger person than I am said “You can be too compassionate.” I was like, “I’m sorry?” She responded, “Well, if you give too much of yourself away, then you don’t have any compassion for yourself.” I could not understand this. The more we talked about it, the more I understood what she was talking about. “That is not my experience. My experience is if you do an act of compassion, it actually comes back to you. It’s not that it takes anything away from you, but it ‘s what actually enriches you as maybe even more than the person that you feel you’re doing it for.”

I left wondering if Jane has any idea how her focus on children and learning have enriched generations of “children.” And I hope it has all enriched her life, maybe even more. This walk reminds me that kids don’t need answer keys in the back of the book… things are rarely right or wrong exclusively… and wrong is just a more enriching path of learning. There is no wrong way to be a maker… no wrong way to walk through a children’s museum… no wrong way to observe the moon.